Statistics: How PostgreSQL Counts Without Counting

Part 1: A bird's-eye view into PostgreSQL statistics

Table of Contents

Series Introduction

Understanding the Query Planner

The Role of Statistics

Setup

Demo: Without Statistics

Exploring pg_class

Creating an Index

Importance of Accurate Statistics

Gathering Statistics

Analyzing the Table

Utilizing EXPLAIN ANALYZE

Defining A Utility Function

ConclusionsSeries Introduction

In this two-part article series, we’ll explore how important data insights help PostgreSQL make smart decisions to keep everything running smoothly. Through easy-to-follow examples, we’ll show you the benefits of regular database maintenance and how it prevents issues before they arise. We’ll also discuss what happens when these data statistics become outdated and share simple ways to keep your database performing its best automatically. By the end of this series, you’ll have a clear and enjoyable understanding of how PostgreSQL uses statistics to optimize performance and how you can fine-tune your own databases for maximum efficiency. Join us on this journey to make the most out of your PostgreSQL databases and ensure they run smoothly and effectively!

The source code for queries in this article can be found in this GitHub repository: https://github.com/msdousti/pg-analyze-training.

Understanding the Query Planner

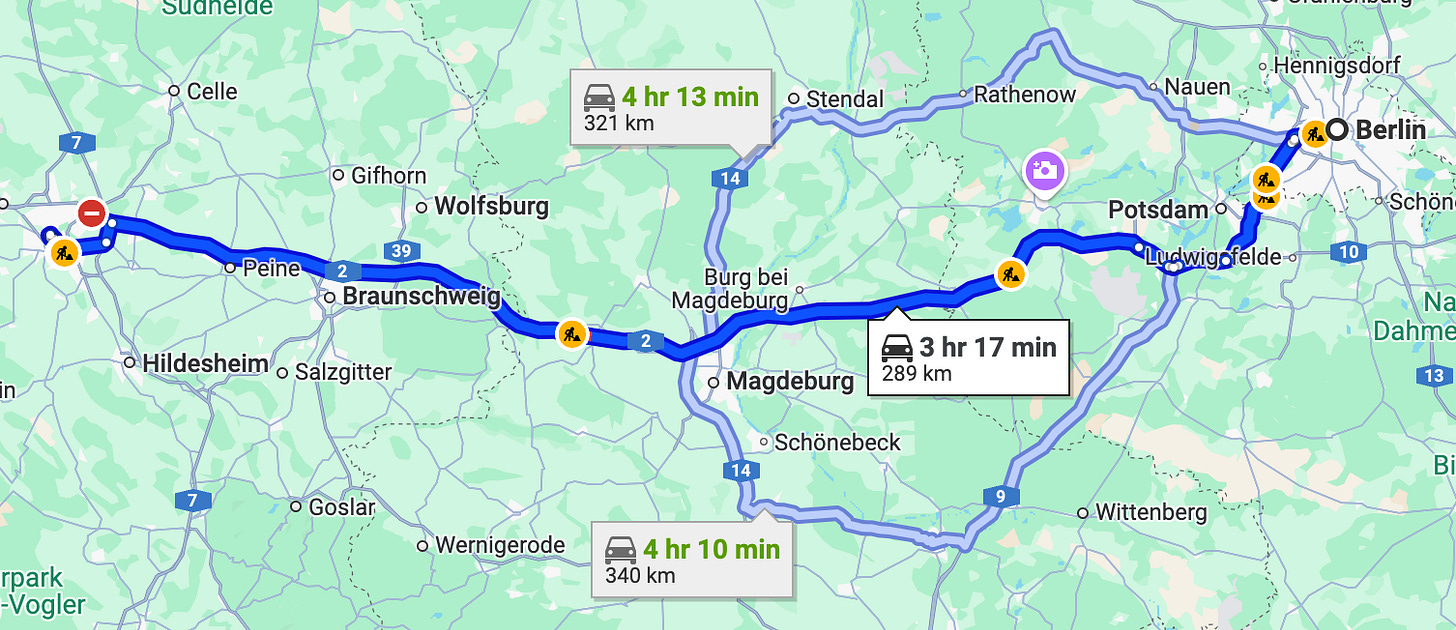

Let’s plan for a trip: We’d like to travel from Berlin to Hanover. Which route should we take? Asking Google Maps, it shows us three routes:

The suggested one would take 3 hr 17 min.

The other two routes are supposed to take 4 hr 13 min and 4 hr 10 min.

How does Google Maps know these estimates? Well, it is based on past (driver) experiences and data it has collected and analyzed. In simple terms, it’s based on statistics, that is regularly updated.

Now, would you trust Google Maps had I told you it hasn’t updated its statistics in 10 years? Probably not. In the meantime, new roads may have been built, old roads may have been closed, traffic jams and construction sites could have been formed, etc.

Similarly, PostgreSQL’s query planner must decide the most efficient way to execute a query. It evaluates different execution plans — like choosing between a sequential scan or using various indexes. When joining multiple tables, it considers different join algorithms and orders of joining tables. Once PostgreSQL selects a plan, it commits to it without the ability to backtrack, much like choosing a travel route and sticking with it despite unforeseen traffic.

The Role of Statistics

PostgreSQL relies heavily on statistics to make these decisions. Statistics are based on data that PostgreSQL has previously gathered about the table data. Without up-to-date statistics, PostgreSQL may make inaccurate estimations about row counts and data distribution, leading to inefficient query plans.

Setup

We’ll use schema analyze_training for this whole series. The following snippet drops the schema (if exists) and then creates it, then sets the PostgreSQL search path to this schema. In this way, we have a clean slate to begin with:

drop schema if exists analyze_training cascade;

create schema analyze_training;

set search_path to analyze_training;Demo: Without Statistics

To demonstrate this, I created a table t with a single integer column n and turned off autovacuum. Turning off autovacuum is a setting I strongly advise against, but it’s necessary for this demonstration to show my point about the vitality of gathering statistics. I inserted 1,000 rows with values 0 to 999 modulo five, totaling ~200 of each integer value between 0 and 4.

create table t(n)

with (autovacuum_enabled = off)

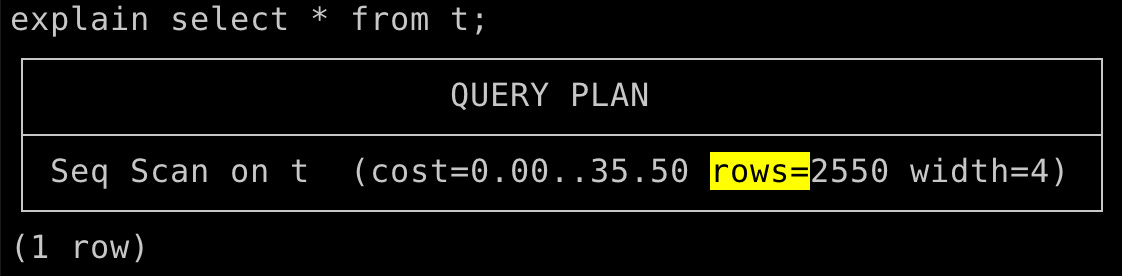

as select mod(generate_series(0, 999), 5);Next, we will use PostgreSQL explain keyword to see the query plans. We are specially interested in the rows=N part of the plan, where it estimates the number of returned rows.

Running a query like SELECT * FROM t; resulted in PostgreSQL estimating 2,550 rows instead of the actual 1,000. Queries such as SELECT COUNT(*) FROM t WHERE n = 0; estimated 13 rows instead of the actual 200, and SELECT COUNT(*) FROM t WHERE n = 10; also incorrectly estimated 13 rows, despite knowing there are no such entries. This highlights how disabling statistics leads PostgreSQL to rely on flawed heuristics.

explain select * from t;

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..35.50 rows=2550 width=4) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain select * from t where n = 0;

┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..41.88 rows=13 width=4) │

│ Filter: (n = 0) │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain select * from t where n = 10;

┌───────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├───────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..41.88 rows=13 width=4) │

│ Filter: (n = 10) │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────┘Exploring pg_class

PostgreSQL stores metadata about tables in the pg_class system table. When autovacuum is disabled, querying pg_class for table t returned -1 for the number of tuples, indicating PostgreSQL has no accurate information about the table’s row count due to the lack of statistics.

select reltuples from pg_class

where oid = 't'::regclass;

┌───────────┐

│ reltuples │

├───────────┤

│ -1 │

└───────────┘Creating an Index

Creating an index on column n updated pg_class to reflect the accurate row count.

create index t_n_idx on t(n);

select reltuples from pg_class

where oid = 't'::regclass;

┌───────────┐

│ reltuples │

├───────────┤

│ 1000 │

└───────────┘Queries like SELECT * FROM t; now correctly estimated 1,000 rows. However, specific queries like SELECT COUNT(*) FROM t WHERE n = 0; still provided inaccurate estimates (now 5 instead of 200). This demonstrates that while indexes improve some aspects, they don’t always resolve issues related to missing or stale statistics.

explain select * from t;

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..15.00 rows=1000 width=4) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain select * from t where n = 0;

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Bitmap Heap Scan on t (cost=4.19..9.52 rows=5 width=4) │

│ Recheck Cond: (n = 0) │

│ -> Bitmap Index Scan on t_n_idx (cost=0.00..4.19 rows=5 width=0) │

│ Index Cond: (n = 0) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain select * from t where n = 10;

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Bitmap Heap Scan on t (cost=4.19..9.52 rows=5 width=4) │

│ Recheck Cond: (n = 10) │

│ -> Bitmap Index Scan on t_n_idx (cost=0.00..4.19 rows=5 width=0) │

│ Index Cond: (n = 10) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘Importance of Accurate Statistics

In real-world scenarios, inaccurate statistics can lead to significant performance issues. I’ve witnessed my fair share of incidents where stale statistics caused queries that typically ran in milliseconds to take minutes or even hours. More on this later!

Gathering Statistics

Analyzing the Table

Let’s recreate the table as before, but without the index:

drop table t;

create table t(n)

with (autovacuum_enabled = off)

as select mod(generate_series(0, 999), 5);Initially, pg_class has no knowledge of row counts. Also, there is no statistics about the table in pg_stats view (This is a very useful view that PostgreSQL provides on the underlying catalog table pg_statistics):

select reltuples from pg_class

where oid = 't'::regclass;

┌───────────┐

│ reltuples │

├───────────┤

│ -1 │

└───────────┘

select * from pg_stats

where schemaname = 'analyze_training' and tablename = 't';

(0 rows)Running ANALYZE on the table allowed PostgreSQL to gather accurate statistics.

analyze t;

select reltuples from pg_class

where oid = 't'::regclass;

┌───────────┐

│ reltuples │

├───────────┤

│ 1000 │

└───────────┘

select * from pg_stats

where schemaname = 'analyze_training' and tablename = 't';

┌─[ RECORD 1 ]───────────┬───────────────────────┐

│ schemaname │ public │

│ tablename │ t │

│ attname │ n │

│ inherited │ f │

│ null_frac │ 0 │

│ avg_width │ 4 │

│ n_distinct │ 5 │

│ most_common_vals │ {0,1,2,3,4} │

│ most_common_freqs │ {0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2} │

│ histogram_bounds │ ∅ │

│ correlation │ 0.20479521 │

│ most_common_elems │ ∅ │

│ most_common_elem_freqs │ ∅ │

│ elem_count_histogram │ ∅ │

│ range_length_histogram │ ∅ │

│ range_empty_frac │ ∅ │

│ range_bounds_histogram │ ∅ │

└────────────────────────┴───────────────────────┘The pg_stats view showed detailed statistics per column, including schema name, table name, attribute name, percentage of nulls, average width, most common values, their frequencies, and histogram bounds. Correlation between data values and their physical storage was also assessed. In particular:

most_common_valsare{0,1,2,3,4}, which are exactly the values we inserted.most_common_freqsare{0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2}, meaning each common value is present at roughly 20% of the rows.histogram_bounds: We’ll discuss it in Part 2 of this article.

(Other stats — such as most_common_elems — are for non-scalar columns like arrays. We don’t discuss them here.)

It’s important to know that statistics are gathered per single table column. In other words, each column of a table has its own separate statistics, independent of other columns.

Showing query plans after statistics are gathered:

explain select * from t;

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..15.00 rows=1000 width=4) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain select * from t where n = 0;

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..17.50 rows=200 width=4) │

│ Filter: (n = 0) │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain select * from t where n = 10;

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..17.50 rows=1 width=4) │

│ Filter: (n = 10) │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────┘PostgreSQL now accurately recognized the number of tuples in the table and provided correct estimates for queries:

There are 1,000 rows in the table;

Exactly 200 of them are 0;

Exactly 0 of them are 10. PostgreSQL estimates 1, as estimating 0 would cause the query not to be executed at all. Since statistics are just estimate, the planner never estimates 0 rows, unless it can mathematically prove that there are no rows to be returned:

explain select * from t where 1=0;

┌──────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├──────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Result (cost=0.00..0.00 rows=0 width=0) │

│ One-Time Filter: false │

└──────────────────────────────────────────┘Utilizing EXPLAIN ANALYZE

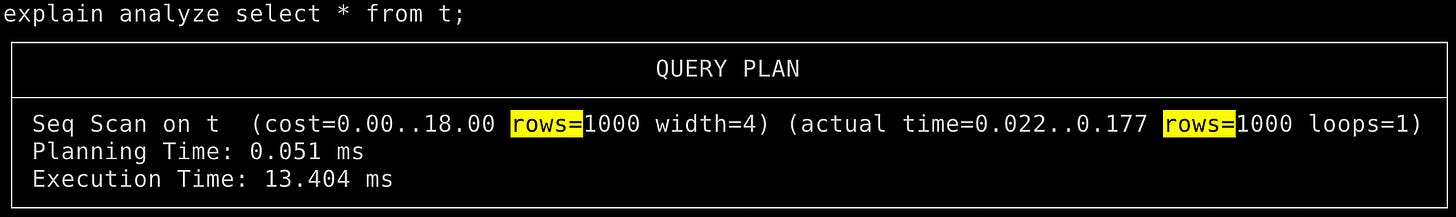

Using EXPLAIN ANALYZE actually runs the query, allowing you to see the estimated versus actual row counts for queries. (Look at the rows=N in the first parenthesis and the second one in the query plan).

For instance:

explain analyze select * from t;

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..15.00 rows=1000 width=4) (actual time=0.025..0.095 rows=1000 loops=1) │

│ Planning Time: 0.069 ms │

│ Execution Time: 0.136 ms │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain analyze select * from t where n = 0;

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..17.50 rows=200 width=4) (actual time=0.013..0.123 rows=200 loops=1) │

│ Filter: (n = 0) │

│ Rows Removed by Filter: 800 │

│ Planning Time: 0.042 ms │

│ Execution Time: 0.141 ms │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

explain analyze select * from t where n = 10;

┌────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ Seq Scan on t (cost=0.00..17.50 rows=1 width=4) (actual time=0.100..0.100 rows=0 loops=1) │

│ Filter: (n = 10) │

│ Rows Removed by Filter: 1000 │

│ Planning Time: 0.063 ms │

│ Execution Time: 0.110 ms │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘This command provides both the query plan and the actual execution details, helping you understand the accuracy of PostgreSQL’s estimations based on the gathered statistics.

Using

EXPLAIN ANALYZEon data modification queries likeINSERTorUPDATEcan be dangerous, because the query is actually executed against your data. If you only intend to know the query plan and its actual running time, without modifying the data, wrapEXPLAIN ANALYZEin aBEGIN;...ROLLBACK;block, and note thatROLLBACKcan create dead rows (more on dead rows later!)

Defining A Utility Function

To streamline the process of comparing estimates with actual execution, I defined a utility function that executes EXPLAIN ANALYZE in JSON format:

explain (analyze, format json)

select * from t;

┌─────────────────────────────────────┐

│ QUERY PLAN │

├─────────────────────────────────────┤

│ [ │

│ { │

│ "Plan": { │

│ "Node Type": "Seq Scan", │

│ "Parallel Aware": false, │

│ "Async Capable": false, │

│ "Relation Name": "t", │

│ "Alias": "t", │

│ "Startup Cost": 0.00, │

│ "Total Cost": 15.00, │

│ "Plan Rows": 1000, │

│ "Plan Width": 4, │

│ "Actual Startup Time": 0.020, │

│ "Actual Total Time": 0.158, │

│ "Actual Rows": 1000, │

│ "Actual Loops": 1 │

│ }, │

│ "Planning Time": 0.072, │

│ "Triggers": [ │

│ ], │

│ "Execution Time": 0.240 │

│ } │

│ ] │

└─────────────────────────────────────┘The function extracts relevant information like node type, planned rows, and actual rows. This function simplifies the analysis and makes it easier to assess the accuracy of PostgreSQL’s statistics.

create type pln as (scan text, estimate text, actual text);

create or replace function c(query text)

returns pln language plpgsql as $$

declare

jsn jsonb;

plan jsonb;

begin

execute format('explain (analyze, format json) %s', query)

into jsn;

select jsn->0->'Plan' into plan;

return row(plan->>'Node Type', plan->>'Plan Rows', plan->>'Actual Rows');

end;

$$;Example usage:

select * from c('select * from t');

┌──────────┬──────────┬────────┐

│ scan │ estimate │ actual │

├──────────┼──────────┼────────┤

│ Seq Scan │ 1000 │ 1000 │

└──────────┴──────────┴────────┘

select * from c('select * from t where n=0');

┌──────────┬──────────┬────────┐

│ scan │ estimate │ actual │

├──────────┼──────────┼────────┤

│ Seq Scan │ 200 │ 200 │

└──────────┴──────────┴────────┘

select * from c('select * from t where n=10');

┌──────────┬──────────┬────────┐

│ scan │ estimate │ actual │

├──────────┼──────────┼────────┤

│ Seq Scan │ 1 │ 0 │

└──────────┴──────────┴────────┘Credit: The function is inspired by the

count_estimatefunction from PostgresSQL Count Estimate wiki page.

We will use this utility function in Part 2!

Conclusions

Mastering the query planner is essential for optimizing database performance and ensuring efficient data retrieval. This article highlighted the pivotal role that accurate statistics play in helping the query planner decide on the cost of the chosen plan.

In part 2, we will build on the concepts discussed here. We’ll look at histograms, vacuum, dangers of stale statistics, and multi-column statistics. Stay tuned!